- Home

- Hualing Nieh

Mulberry and Peach Page 2

Mulberry and Peach Read online

Page 2

A torch flares up along the river. A paddlewheel steamboat, blasted in half by the Japanese, lies stranded in the dark water like a dead cow. Along the river several lamps light up. Near the shore are several old wooden boats. Our boat, crippled while rounding the sandbanks at New Landslide Rapids, is tied up there for repairs.

The village of Tai-hsi is like a delicate chain lying along the cliffs. There is no quay along the river. When you disembark you have to climb up steep narrow steps carved out of the cliff. When I crawled up those steps, I didn’t dare look up at the peak, or I might have fallen back into the water, a snack for the dragon.

A torch bobs up the steps. After a while I can see that there is a man on horseback coming up the steps, carrying a torch. The torch flashes under my window and I glimpse a chestnut-coloured horse.

Lao-shih and I ran away together from En-shih to Pa-tung. I am sixteen and she is eighteen. We thought we could get a ship out of Pa-tung right away and be in Chungking in a flash. When we get to Chungking, the war capital, we’ll be all right, or at least that’s what Lao-shih says. She patted her chest when she said that to show how certain she was. She wears a tight bra and tries to flatten her breasts, but they are as large as two hunks of steamed bread. She said, ‘Chungking, it’s huge city. The centre of the Resistance! What are you scared about? The hostel for refugee students will take care of our food, housing, school and a job. You can do whatever you want.’ We are both from the remote mountains of En-shih and are students at the Provincial High School. Whatever I don’t know, she does.

When we got to Pa-tung, we found out that all the steamships have been requisitioned to transport ammunition and troops. Germany has surrendered to the Allies and the Japanese are desperately fighting for their lives. A terrible battle has broken out again in northern Hupeh and western Hunan. There weren’t any passenger ships leaving Patung, only a freighter going to Wu-shan, so we took that. When we arrived in Lashing, we happened upon an old wooden boat which carried cotton to Feng-chieh, so we took that.

Towering mountains above us, the deep gorge below. Sailing past the Gorge in that old boat was really exciting, but it cracked up on the rocks of New Landslide Rapids and is now at Tai-hsi for repairs.

Lao-shih just went out to find out when the boat will be repaired and when we can sail. A unit of new recruits is camped out in the courtyard of the inn. Tomorrow they’ll be sent to the front. I sit by the window and undress, leaving on only a bra and a pair of skimpy panties. The river fog rolls in and caresses me, like damp, cool feathers tickling my body. The river is black and I haven’t lit the lamp. I can’t see anything in front of me. The few lamps along the river go out one by one. Before me the night is an endless stretch of black cloth, a backdrop for the game I play with my griffin:Griffin, griffin, green as oil

Two horns two wings

One wing broken

A beast, yet a bird

Come creep over the black cloth

And the griffin comes alive in my hand, leaping in the darkness. The wings outstretched, flapping, flapping.

‘Hey.’

I turn. Two eyes and a row of white teeth flash at me from the door. I scream.

‘No, don’t scream. Don’t scream. I was just drafted and tomorrow I’m being sent to the front. Let me hide in your room just for tonight.’

I can’t stop screaming. My voice is raw. When I finally stop, he is gone, but two eyes and that row of teeth still wink at me in the dark. A whip cracks in the courtyard.

‘Sergeant, please, I won’t do it again. I won’t run away again . . .’

The shadows of the soldiers in the courtyard appear on the paper window. The man hangs upside down, head twitching. Beside him, a man snaps a whip and a crowd of heads looks up.

‘Lao-shih,’ I pause and stare at the jade griffin in my hand. One of its wings is cracked. ‘I don’t want to go to Chungking. I want to go home.’

‘Chicken. You getting scared?’

‘No, it’s not that.’

‘You can’t turn back. You have to go, even if you have to climb the Mountain of Knives. That’s all there is to it, you know what I mean. Anyway, you can’t go back now. Everyone in En-shih knows you’ve run away by now. Your mother won’t forgive you either. You know when she was drunk, she would beat you for no reason, until you bled. She will kill you if you go back.’

‘No. She wouldn’t do anything to me. As soon as I ran away, I stopped hating her. And I still have Father. He’s always been good to me.’

‘Little Berry, don’t get mad, but what kind of a man is he, anyway? Can he manage his family? He can’t even manage his own wife. He lets her get away with everything while he sits in his study, the old cuckold, meditating. You call that a man? However you look at it, he’s not a man.’ She starts laughing. ‘You said so yourself. Your father wounded his “vital part” during the campaign against the warlords . . .’ She is laughing so hard she can’t go on.

‘Lao-shih, that’s not funny.’

‘So why can’t a daughter talk about her father’s genitals?’

‘Well, I always felt . . .’ I rub the jade griffin.

‘You always felt guilty, right?’

‘Mm . . . but not about his vital part!’ I start laughing. ‘I mean this griffin I’m holding. I stole it when I left. Father’s probably really upset about it.’

‘With all these wars and fighting, jewels aren’t worth anything anyway. Besides, it’s only a piece of broken jade.’

‘This isn’t an ordinary piece of jade, Lao-shih. This jade griffin was passed down from my ancestors. Originally jade griffins were placed in front of graves in ancient times to scare away devils. My great-grandfather was an only son, really sickly as a child, and he wore this piece of jade around his neck and lived to be eighty-eight. When he died he ordered that it be given to my grandfather and not used as a burial treasure. My grandfather was also an only son. He wore it his whole life and lived to be seventy-five. Then he gave it to my father who was also an only son. He wore the griffin as a pendant on his watch chain. I’ll always remember him wearing a white silk jacket and pants, a gold German watch in one pocket and the jade griffin in the other pocket, and the gold chain in between, swishing against the silk. When he wasn’t doing anything, he’d take it from his pocket and caress it and caress it and it would come alive. You know what I thought about when he did that?’

Lao-shih doesn’t say anything.

‘I would think about what my great-grandfather looked like when he died. Isn’t that strange? I never even saw him. I would imagine him wearing a black satin gown, black satin cap, with a ruby red pendant dangling from the tip of the cap, black satin shoes. He would have a squarish head, big ears, long chin, and thick eyebrows, his eyes closed, lying in the ruby red coffin with the jade griffin clasped in his hands.’

‘Now your younger brother is the only son. Your father will pass it along to him, and you won’t get it.’

‘Don’t I know it. I wasn’t even allowed to touch it. I used to get so upset, I would cry for hours. That was before the war when we still lived in Nanking. Mama took the jade griffin from my father’s pocket. She said she should be the one to take care of the family heirloom and that father would only break it sooner or later by playing with it. She had it made into a brooch. I really liked to play with cute things like that when I was a kid, you know? I always wanted to wear the brooch. One day I saw it on Mother’s dresser. I reached for it and she slapped me and by accident I knocked it to the floor. One of the wings was chipped and she shut me in the attic.

‘It was pitchblack in the attic. I knelt on the floor crying. Then I heard a junk peddler’s rattle outside. I stopped crying and got up. I crawled out the window and stood on the roof, looking to see where the rattle was coming from. The peddler passed by right outside our house. I took a broken pot from the windowsill and threw it at him, then went back to the attic. He cursed up and down the street. I knelt on the floor giggling hysterically. Then the

door opened.

‘Mother stood in the doorway, the dark narrow staircase looming behind her like a huge shadow. She stood motionless, her collar open, revealing a rough red imprint on her neck. She was wearing the jade griffin.

‘In my head I recited a poem that my father had taught me. It was like a magic spell to me:Child, come back

Child, come back

Child, why don’t you come back?

Why do you come back as a bird?

The bird’s sad cries fill the mountains.

It’s about a stepmother who is mean to her stepson. Her own son turns into a bird. I thought that Mother was my stepmother and that my little brother, was her son. I thought if I said this poem, my little brother would turn into a bird. I decided that one day I would smash the griffin.’

‘But now you want to give it back.’

‘Mmm.’

‘Little Berry, I think it’s great you stole it. Your family loses twice: they lost their daughter and their jade. This time your mother might stop and think. Maybe she will change her ways.’

‘Has the boat been repaired?’

‘Not yet.’

‘God. How long are we going to have to wait here?’

Tai-hsi has only one street, a stone-paved road that runs up the cliff. It’s lined with tea houses, little restaurants, and shops for groceries, torches, lanterns, tow-lines. Lao-shih and I are eating noodles at one of the restaurants. The owner’s wife clicks her tongue when she hears that our boat was crippled at New Landslide Rapids and will be heading for Feng-chieh once it’s repaired.

‘Just wait. New Landslide Rapids is nothing. Further on there’s Yellow Dragon Rapids, Ghost Gate Pass, Hundred Cage Pass, Dragon Spine Rapids, Tiger Whisker Rapids, Black Rock Breakers and Whirlpool Heap. Some are shallow bars, some are flooded. A shallow bar is dangerous when the water is low, a flooded bar is dangerous when the water is high. If you make it past the shallow bar, you won’t make it past the flooded one. If you get past the flooded one, you’ll get stuck on the shallow one . . .’

Lao-shih drags me out of the restaurant.

‘Little Berry, I know if you hear any more of that kind of talk, you won’t want to go on to Chungking.’

‘I really don’t want to get back on that boat. I want to go home!’

Lao-shih sighs. ‘Little Berry, if that’s how you feel, why did you ever decide to come in the first place?’

‘I didn’t know it was going to be like this.’

‘All right. Go on back. I’ll go to Chungking all by myself.’ She turns away and takes off, climbing up the stone-paved path.

I have to follow. We get to the end of the path and stop. Before us is a suspension bridge. Beyond it are mountains piled on mountains, below, the valley. There’s a stream in the valley and the waters are roaring. Even from this high on the cliff, we can hear the sound of water breaking on the rocks. Six or seven naked boys are playing in the stream below, hopping around on the rocks, skipping stones in the water, swimming, fishing. One of them sits on a rock, playing a folk song about the wanderer, Su Wu, on his flute. There is a heavy fog. The mountains on the other shore are wrapped in mist and all that is visible is a black peak stabbing the sky.

‘What do you say? Shall we cross the bridge?’ Someone comes up behind us.

It’s the young man who boarded with us at Wu-shan. We nicknamed him Refugee Student. He’s just escaped from the area occupied by the Japanese. When he gets to Chungking, he wants to join the army and fight the Japanese. He is barechested, showing off his sun-tanned muscular chest. This is the first time we’ve ever spoken. But I dreamed about him. I dreamed I had a baby and he was the father. When I woke up my nipples itched. A baby sucking at my nipples would probably make them itch like that, itch so much that I’d want someone to bite them. I had another dream about him. It was by the river. A torch was lit, lighting the way for a bridal sedan to be carried up the narrow steps. The sedan stopped under my window. I ran out and lifted up the curtain and he was sitting inside. I told that dream to Lao-shih. She burst out laughing and then suddenly stopped. She said that if you dream of someone riding in a sedan chair, that person will die. A sedan chair symbolises a coffin. I said, damn it, we shouldn’t go on the ship with him through the dangerous Chu-t’ang Gorge if he is going to die!

‘I was in the tea house drinking tea and I saw you two looking at the bridge,’ he says.

‘So you’ve got your eye on us,’ says Lao-shih, shoving her hands in the pockets of her black pants and tossing her short hair defiantly. ‘Just what do you want, anyway?’

‘Hey, I was just trying to be nice. I came over intending to help you two young ladies across this rickety worn-out bridge. Look at it, a few iron chains holding up some rotting planks. I just crossed it myself a while ago. It’s really dangerous. When you get to the middle, the planks creak and split apart. The waters roar below you and you’re lost if you fall in.’

‘That’s if you’re stupid enough to try it.’

‘Miss Shih, may I ask what it is about me that offends you?’ Refugee Student laughs.

‘I’m sorry . . . and my name is Lao-shih.’

‘OK, Lao-shih? Let’s be friends.’

‘How about me?’ I say.

‘Oh, you!’ He smiles at me. ‘But I still don’t know your name. Lao-shih calls you Little Berry, kind of a weird name if you ask me . . .’

‘I don’t want you to call me that, either. She’s the only person in the whole world who can call me that. Just call me Mulberry.’

‘OK, Lao-shih and Mulberry. You’ve got to cross this bridge at least once. I just crossed it. It’s a different experience for everyone. I wanted to see what it felt like to be dangling on a primitive bridge above dangerous water.’

‘Well, what’s it like?’

‘You’re suspended there, unable to touch the sky above you or the earth below you, pitch-black mountains all around you and crashing water underneath. You’re completely cut off from the world, as if you’ve been dangling there since creation. And you ask yourself: Where am I? Who am I? You really want to know. And you’d be willing to die to find out.’ He takes a stick and draws two mountain peaks in the dust and joins them with two long thin lines.

A burst of flames shoots up towards us from the valley.

‘Bravo.’ The boys in the valley clap their hands.

‘Hey . . .’ yells Refugee Student, ‘if someone gets killed you’ll pay.’

Lao-shih tugs at his arm telling him that the innkeeper told her never to provoke that bunch of kids. There are eleven of them altogether, thirteen or fourteen years old at the most. They live in the forest on the other side of the bridge. No one knows where they come from, only that they are all war orphans and they live by begging along the Yangtze River. They travel awhile, then rest awhile before going on again. They want to go to Chungking to join the Resistance and save the country from the Japanese. They’ll kill without batting an eye. They killed a man in Pa-tung. The ferry across the river wasn’t running and there was no bridge, so the boys ferried people across. Someone on the boat offended them. They drugged him with some narcotic incense. They dragged him into the forest, cut open his stomach and hid opium inside it. Then they put him in a coffin and pretending they were a funeral procession, they smuggled opium to Wu-shan.

The boys are still laughing and cursing and yelling down the river. The one with the flute climbs up the mountain. His naked body is covered only with a piece of printed cloth frayed into strips. A whistle on a red string dangles on his chest. He leaps onto the bridge, but instead of walking across it, he grabs the iron chains and swings across from chain to chain with the flute clenched in his teeth. He swings to the middle of the bridge, one hand gripping the chain. With his other hand he takes the flute from between his teeth and trills a long signal to the kids in the valley below.

He shouts, ‘Hey, you sons of bitches. How about a party tonight?’

‘We’ll be there in a minute. Let’s ca

tch some fish and have a feast.’

He grips the chain and swings on. The frayed cloth flutters as he moves.

The boys scramble up the mountain. One by one they leap onto the bridge and swing across to the other side. They’re naked as well, except for the rags around their waists. It’s almost dark. The fog is rolling in. They swing on and on, disappearing into the fog.

‘Hey, you guys, swing across.’ Their voices call to us through the fog.

‘OK, here I come,’ Refugee Student jumps onto the bridge and swings across.

‘Come on!’ says Lao-shih tossing her head and walking out onto the bridge. ‘We can’t let them think we’re chicken.’

I go with her onto the bridge. The roar of the water gets louder. The bridge sways violently. I grip the railing and wait for it to stop swinging.

Dangling from the chain, Refugee Student turns and yells: ‘Don’t stop. Come on. There’s no way to stop it. The faster it sways, the faster you have to walk. Try to walk in time to the swaying.’ I grip the railing and move forward. I sway the bridge and the bridge sways me. I walk faster. The mountain, the water, the naked boys, Refugee Student, all fuse together in my vision. I want to stop but I can’t and I start to run to the other side while the bridge sways and swings.

Finally our boat is repaired. Lao-shih and I climb aboard singing ‘On the Sunghua River’, a song about the lost homeland. Twelve oarsmen pull at the oars; the captain at the rudder. There are six passengers on board: an old man, a woman in a peach-flowered dress with her baby, Lao-shih, me, and that crazy refugee student.

We get through Tiger Whisker Rapids.

Rocks jut up from Whirlpool Heap. Black Rock Breakers is a sinking whirlpool. We get through it.

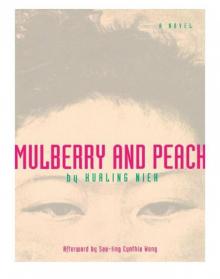

Mulberry and Peach

Mulberry and Peach